Running Read online

RUNNING

S. BRYCE

RUNNING

Novel by S. Bryce

Copyright©2014 S. Bryce

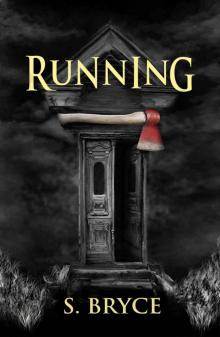

Cover Art by DaCostaArtDesign.com Copyright © 2014

Kindle Edition

This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Chapter 1

Thud

I shiver in the cold night air and drape my arm around, my little brother, Tosh’s shoulder. In my other hand, I hold the shovel I used to dig our sister Ellie’s grave.

Mannis tightens the ragged sheet around her body. With thick clumsy hands, he lays her corpse to rest in the wet soil.

Thud! That’s the noise her corpse makes as it hits the ground.

Thud! Just like my heart.

Tosh flinches at the sound.

It must be rainwater trickling down my face. Yes, I remember. It was raining not so long ago and the wind blew leaves across the lawn to lash at my face. That’s why my eyes are stinging and my cheeks are numb.

My fingers fumble over Tosh’s lips and over the bridge of his tiny nose, sweeping across his tear-stained cheeks. I cover his mouth to stop him from screaming again. I don’t want Mannis’s temper to flare up. Not tonight.

I hide my own grief, it’s silent, aching, tearing at my insides.

I’ve dug a hole deep enough for us all.

Mannis mops his brow with the cuff of his shirt. He closes his eyes. He crawls out of Ellie’s grave, his fat body swaying, and for one second, I think he’s going to retch. His lips twitch and his grey eyes roll in their sockets. He doubles over, grabs hold of his knees, takes a deep breath and then straightens. He takes the shovel from me. I watch him scoop the damp earth over her body.

I say a mute prayer and hug Tosh closer to me. And then without looking back, I lead Tosh away from our sister’s grave and into the bungalow.

I knew she’d never make it.

* * *

Chapter 2

Mannis the Bear

Four days earlier, on the 3rd of October 1983, we celebrated Ellie’s sixth birthday.

It was Saturday. The sun peeped out through the dark clouds. We sang happy birthday to her as loud as we dared. I persuaded her to blow out the candles on her imaginary cake with her cold blue lips. She wore her own blue jeans that day and her pink jumper.

She loved pink.

Tosh spent ages traipsing through the fields looking for pink flowers to give to her. He couldn’t find any. He returned, blurry-eyed and covered in scratches, having eventually settled on a bunch of wild daisies. He gave Ellie six kisses to make up for it, three on each of her hollow cheeks.

And what did I do? I plaited her shoulder-length hair into pigtails. I told her how cute she looked and how much I loved her. I told her a story, one that I’d made up, about an enormous grizzly bear that lived in the woods. She had heard it before. I thought I’d change it up a little.

The bear had no friends because everyone in the village was afraid of him. Then one day, the bear met a little girl, the spitting image of Ellie. She had big brown eyes and curly brown hair. Her name was Eleanor and she and the bear became the firmest of friends.

She tried to laugh, but coughed instead when I told her the bear’s name was Mannis.

I knew she’d never make it.

* * *

Chapter 3

Waiting

The hospital’s forty miles away.

Anyone of us could have gone for help. If we had wanted to…only…none of us really want to leave the bungalow.

Mannis waited with me on the long twisted road; a good hour’s walk from the bungalow. He held Ellie in his arms like a newborn. She couldn’t walk. She couldn’t talk. We sat and waited for an hour on the grass verge. We saw no one. That one hour was more than enough for Mannis. He turned back, grumbling that he was asking for trouble. He was afraid of what people would say if they saw a grubby fat man on the roadside with two children, afraid of what they might do.

I believe I could have walked those forty miles with Ellie in my arms, if I’d have found the courage. Instead, I sat and waited on my own, watching the shadows erupt as the darkness fell around me. It didn’t seem to matter that I hadn’t brought a torch with me. I can spot a car’s headlights a mile off and I’m not afraid of the dark.

Although after a while, every little noise startled me, from the chirping crickets in the grass to the light breeze rustling the trees. I kept telling myself, I have no choice but to endure this. I placed my hands over my ears and waited.

Later, Mannis came out on the road and hauled me back inside. I think I may have hit him because in the space of a few hours, a red and black blotch appeared on his right cheek.

The next day, I went out alone to the roadside and again the day after that.

I kept going out. I can’t count the number of days I sat huddled on my flattened patch of grass, waiting.

But I clearly remember rising early, determined to set out before anyone could stop me. I was terrified and I didn’t want Ellie or Tosh to see me crying.

As soon as I was outside, I’d cry until I nearly choked. The crying became something of an indulgence; wearing me out, stripping every fibre of strength I had left. In the end, I made a conscious decision to stop crying. Crying wasn’t going to help Ellie.

One day a prune-faced woman pulled up in a red Ford pick-up truck.

Her hands reminded me of an eagle’s talons, most inhuman like, and her neck was like a worn piece of twisted rope. Her silvery-white hair was piled on top of her head and I could have sworn her eyes were yellow.

She looked me up and down when I told her my little sister was sick and that we needed a ride to the hospital.

Not wanting to frighten her away, I tried my best to sound calm and ‘normal’, but it was hard because my voice was all shaky. I hadn’t long stopped crying.

‘She’s up the-the road. If you could take me, p-please.’

She wouldn’t listen. She asked how old I was.

‘Eighteen,’ I said. I’ll turn seventeen this year.

Then she asked my name. My first name is Celia. No one calls me that. It’s a girlie name, way too timid for me. Mum hardly ever called me Celia and my dad used to call me Kat, which I hate.

‘Kate,’ I told her. My middle name is Katherine.

I knew I didn’t smell so good because I hadn’t washed in a while.

The prune-faced woman held her nose, took hold of the bottom of my sweater with her claw-like talons and tried to drag me into the back of her stuffy red truck.

I never got in.

* * *

Chapter 4

The Woodcutter

Mannis lumbers in, ashen-faced. He bangs the front door shut and flings down the shovel.

Our front door is dingy white. The upper part is made from frosted glass. The bottom of the door is splintered and waterlogged.

The strong draught seeping in from under the door chills me to the marrow, yet I can’t bring myself to move.

Mannis wrings out the bottom of his muddy, sweat drenched shirt, his eyes fixed on me. He’s wondering what I’m thinking. He’ll never ask. He’s not big on emotion or ‘kids stuff’ as he likes to call it, although I know he’s fond of Tosh and I in his own way. He shouts and swears at us, but he doesn’t hit us like he does Saul, the other kid in our bungalow.

I sit in the hall, resting against the damp and mouldy wall.

Our bungalow is way out in the country in a place called Medswell. It’s a huge building with a flaking grey stone exterior, a flat leaky roof and shattered windows. T

he ceilings are high, and when it rains the water drains through it like a sieve.

Tosh slumps across my lap, whimpering. I stroke his matted hair. I only combed it yesterday.

‘Is the woodcutter out?’ I ask Mannis.

‘Get in the warm,’ he replies in a gruff voice. He waddles past me into the kitchen where a wood-burning stove is lit. It’s the one place in the bungalow that’s warm.

My mind always drifts to the woodcutter when I’m upset about something. I use him as a mask. The woodcutter has nothing to do with us, nothing to do with our… situation. Mannis doesn’t answer me.

Sometimes I catch a glimpse of the woodcutter chopping at the sorry trees at the bottom of our lawn. I see the blade of his axe flash white in the sunlight. I never see his face. He wears a wide-brimmed hat and when he lifts his head to the sky, his face is nothing but a green and brown blur among all those trees.

Our lawn is vast; as big as a football pitch Mannis reckons, but I don’t know how big a football pitch is supposed to be. I imagine the woodcutter living in a thatched cottage with his wife and two children. I don’t know why. Perhaps they have dog and a rabbit, maybe even a horse.

Mannis told us to stay away from the woods at the bottom of the lawn in case somebody sees us and reports us to the authorities, the police, or both.

I hitched us a lift to Medswell to get away from the Authorities and the police.

I don’t want anyone to split us up. That’s what happened to a girl in my class. Ann Maxwell was her name. Ann and her two younger brothers were orphans. Their parents died in a car accident. They had to go into a care. The Authorities placed Ann in a children’s home in Portsmouth and her two brothers went to a home in Eastbourne.

I remember the menacing look Mannis gave us when we showed up at the front door of the bungalow. “A couple of nights and no more,” he said, wrenching the gold-plated chain from my neck. “You’re not my responsibility.”

We didn’t ask him to stay and he’s not asked us to go.

We’ve lived here undiscovered for nearly six months.

Animals outnumber humans in Medswell. The total village population is thirty-two or it was the last time I checked the library records. Of course, no one in the bungalow’s been counted. No one knows we’re here.

Saul appears. He sits down beside me, bringing one skinny leg to his chest and straightening the other. Saul’s a year older than me. At six foot; he’s roughly a foot taller than I am. He has unusually long eyelashes and elfish ears. His deep green eyes are like two murky ponds, sad and yearning. I know he’s thinking of something to say to me, he just doesn’t know what. And I can’t help him. He tugs at the green woolly hat covering his mop of reddish brown hair and then he scratches at the purplish rash on his fingers that he’s had since the day I got here. He’s dressed in a worn leather jacket, black jeans and a t-shirt. His neck is hidden under a chocolate-brown scarf.

‘I left you some soup,’ he says, tugging at the woolly tassels on his scarf.

As you walk through the front door, you’ll find the kitchen on the left and mine, Tosh’s and Ellie’s room on the right.

‘I’m not hungry,’ I reply.

I hadn’t closed the door and my gaze drifts to the crumpled pink blanket in the corner of Our Room. I wonder briefly who owned the blanket before Ellie and who would own it now.

Saul gently strokes the side of my face. His hand feels like ice on my cold skin.

‘Do you want me to bring it?’ He asks, nodding at the blanket.

‘No,’ I say quietly. ‘You can keep it if you like.’

‘I don’t want it,’ he whispers.

‘I’m cold Kate,’ Tosh says, sniffing. He can’t stop shaking. My jeans are soaked through with his tears. I go to take off my blue jumper to give him and notice he’s already wearing it. All I have on is a tatty grey vest. I realise it’s not him that’s shaking, it’s me. Saul takes his jacket off and places it around my shoulders. He helps us both up.

‘Let’s get you in the warm,’ he says.

* * *

Chapter 5

Our Room

Minutes turn to hours; hours turn to days, days to weeks.

I used to mark off the days by drawing a string of lines in green crayon on Our Room wall. That’s how I remembered Ellie’s birthday: Saturday, 3rd October, 1983.

The day Ellie died, I stopped counting.

It no longer matters to me what day of the week it is.

I could work out how many days have passed in my head - if I wanted to. I need only look outside to see when summer is coming and when winter has passed. A crisp bright morning signals spring; golden leaves on the lawn, autumn. The nights are as black as pitch, and in the day, the light streams in through our back window.

It’s strange. I’ve been wandering around in a daze, drifting from room to room, never quite certain where I am. Hands have reached out to touch me and voices have called to me. Until today, I didn’t know where they were coming from.

Today, my brain is switched on. I know where I am. I’m sitting in Our Room.

Our Room has two narrow rectangular windows. The small window nearest the door looks out on to a ten foot hedge and the other, at the back of the room, looks out on to a hill. The hill slopes downwards, obscuring the view of the road.

We don’t have any proper furniture. I’ve overturned a couple of mahogany drawers to use as tables and placed one at each end of the room. I put wick candles on them. We have to rely on candles and torches to light the way for us when it gets dark as we don’t have electricity.

I’ve packed our clothes, books and shoes into black bags and wooden crates, most of our stuff, however, ends up on the floor.

We left our home in Erin town with nothing. Ellie wanted to bring her Barbie doll and Tosh a toy racing car. Mum made them leave their toys behind. The landlord threatened to call the police if we didn’t leave right away. He said mum had been ‘nicking his booze’.

‘We’re not taking any of that rubbish,’ she had said, snatching the doll out of Ellie’s hands. The doll’s head popped right off. I knew mum regretted it the moment we were outside because Ellie wouldn’t stop crying.

‘What do you want me to do about it?’ Mum screamed at all of us. ‘What do you want me to do!’

We found toys in the bungalow, but they’re all twisted and broken and no good at all.

We have plenty of clothes and blankets. We’ve more blankets and sheets than I can count. And clothes are clothes: it doesn’t matter if they don’t fit, just so long as they’re warm.

I’m sitting beneath the crooked window ledge. The cold draught nips my spine. I realise I’ve spent minutes, hours and days staring into space. My eyes are open but I cannot see, and the voice seems so far away. I lift my head, squinting. A light hurts my eyes, not sunlight, but the beam of light streaming from the torch Saul has set by the door.

Saul kneels before me. He has come to talk to me every day since Ellie died.

Today is the day I choose to listen…

* * *

Chapter 6

A New One

‘We’ve got a New One,’ Saul whispers. He stares transfixed at the broken laces on his worn black boots.

I usually leap at the news of a New One. ‘Who are they?’ I’d ask. ‘Where did they come from? What are they on? How’s their head?’

On this occasion, I don’t say anything.

People come and go here all the time. The winter months are the busiest. Heaps of people came in December and January, staying for a night or so before moving on.

Mannis’s cousin Charlie visits once a month. He brings us crates of tinned soup. I think he works in a soup factory because he never brings tins of anything else. He brings bottled beer too, tobacco, the bits of white paper to roll them in, candles, batteries for our torches and crispy see-through toilet paper. Occasionally, he brings pastries: a bag of sausage rolls or Cornish pasties to share with Mannis.

Mannis a

lways complains to Charlie that he wants ‘proper ciggies’ and whiskey. Charlie calls him an ungrateful bastard and after they’ve argued, Charlie goes away cursing and vowing never to come back, except that he always does.

Then there’s this guy called Johnny who has fifteen tattoos on his arms and a nose like a trumpet. Johnny gets easily bored. He likes to pick fights with Mannis from time to time to give himself something to do. He usually shows up every couple of weeks. I haven’t seen him for a while. Perhaps he’s come and gone and I simply haven’t noticed.

Mannis lets Druggies stay for one night; two at the most before he tells them to sling their hook. Drunks stay until the booze runs out and then they stagger into the village for more. Some of them I never see again, most I don’t want to.

Mannis says he’s the one who gets to decide who lives here because he was here first. Actually, Saul was here first, but Mannis chooses to forget that.

Saul’s lived in the bungalow for years. ‘I’ve lived here for years and years,’ he once said, without ever telling me how many.

Saul was here first, followed by Mannis, then Dock, and finally by my brother, sister and I.

Mannis says, ‘This is our home. The rest who come here are lodgers far as I’m concerned and they ain’t staying here for free.’

‘Did you hear me Kate?’ Saul repeats, ‘I said there’s a new one. A man. He scares me.’

With the exception of Dock, I don’t know a man who doesn’t scare Saul.

Saul answers the questions I would normally ask.

‘Rick’s his name,’ he says in his soft whispery voice. ‘He brought two huge bottles of whisky and no food. Mannis will be pleased. His head’s clear enough. He said he comes from Collis Town, that’s the other side of Fenway.’

Running

Running